The theme of the Book of Exodus (סֶפֶר שְׁמוֹת) essentially turns on two great events, namely, the deliverance of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt (i.e., yetzi’at Mitzraim: יְצִיאַת מִצְרַיִם) and the subsequent revelation given at Sinai (i.e., mattan Torah: מַתַן תּוֹרָה). Both of these events, however, are grounded in the deeper theme of God’s faithful love (chesed ne’eman: חֶסֶד נֶאֱמָן) expressed by the blessing of blood atonement (i.e., kapparat ha’dam: כָּפָרָת הַדָּם). With regard to the former, the blood of lamb (as foreshadowed in Eden) was required to cause death to “pass over” (לִפְסוֹחַ) the houses of the faithful of Israel; with regard to the latter, the sacrificial system represented by the Mishkan (i.e., “Tabernacle”) was designed to teach what I call the “korban principle” (i.e., ikaron ha’keravah: עִקָרוֹן הַקרָבָה), that is, that the only way to draw near to God is by means of sacrificial blood offered in exchange for (or in place of) the trusting sinner, as it is stated in the Torah, “For the life of the flesh is in the blood, and I have given it for you on the altar to make atonement for your souls, for it is the blood that makes atonement by the life” (Lev. 17:11), and likewise in the New Testament we read: “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins” (Heb. 9:22).

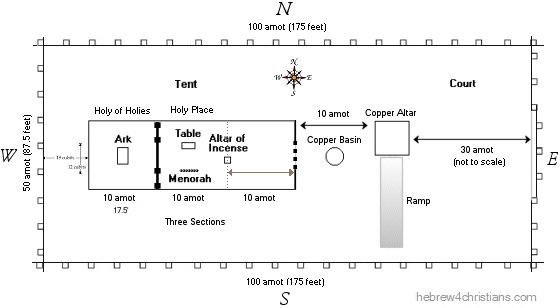

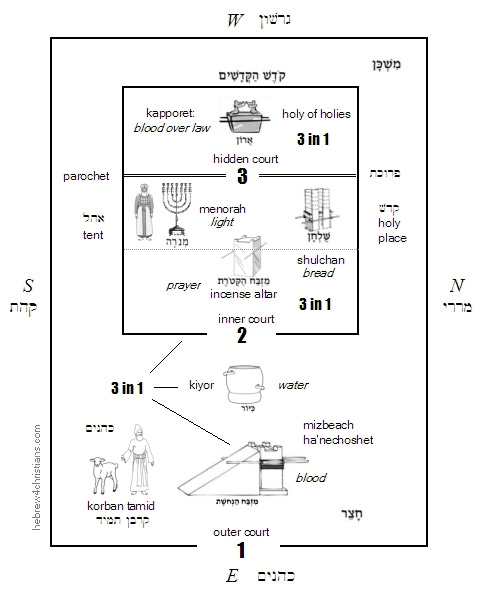

Jewish tradition tends to regard the giving of the law at Sinai to be the goal of the entire redemptive process, a sort of “return from Exile” to the full stature of God’s chosen people. Some of the sages have taken this a step further by saying that God created the very universe so that Israel would accept the law. Such traditions, it should be understood, derive more from rabbinical thinking devised after the destruction of the Second Temple than from the narrative presented in the written Torah itself, since is clear that the climax of the revelation at Sinai was to impart the pattern of the Mishkan (תבנית המשכן) to Moses. In other words, the goal of revelation was not primarily to impart a set of moral or social laws, but rather to accommodate the Divine Presence (i.e., ha’makom: המקום) in the midst of the people. This is not to suggest that the various laws and decrees given to Israel were unimportant, of course, since they reflect the holy character and moral will of God. Nonetheless, it is without question that the Torah was revealed concurrently with the revelation of the Sanctuary itself, and the two cannot be separated apart from “special pleading” and the suppression of the revelation given in the Torah itself... The meticulous account of the Mishkan is given twice in the Torah to emphasize its importance to God. This further explains why Leviticus is the central book of the Torah of Moses. (For more on this, see “The Eight Aliyot of Moses.”)

As we consider these things, however, it is important to realize that underlying the events surrounding deliverance and revelation is something even more fundamental, namely, the great theme of faith (אֱמוּנָה). This theme is our response to God’s redemptive love. God’s love is the question, and our response - our teshuvah - is the answer. The great command is always to "choose life!" We must chose to turn away from the darkness to behold the Light... Jewish tradition states there were many Jews who perished in Egypt during the Plague of Darkness because they refused to believe in God’s love. Likewise, the revelation at Sinai failed to transform the hearts of many Jews because they despaired of finding hope…

As glorious as the redemption and revelation was, then, there was something even more foundational that gave “inward life” to God’s gracious intervention. You must first believe that God loves you and regards you as worthy of His love; you must “accept that you are accepted.” It is your faith that brings you near... This is the “Cinderella Story” of Exodus.

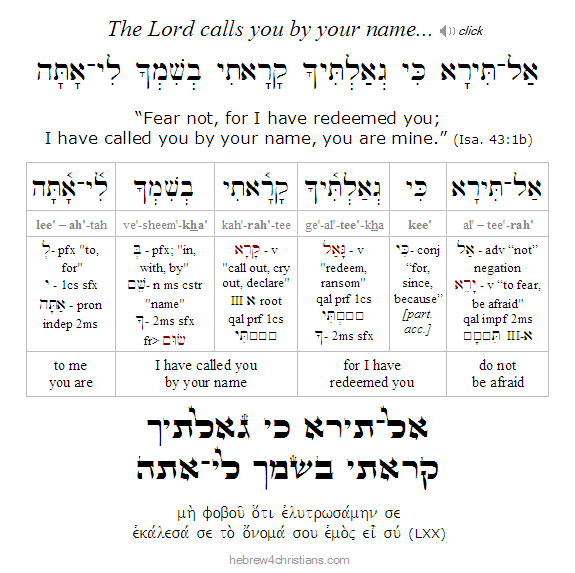

These themes of the Book of Exodus - and really of the Bible itself - will mean little to you unless you willingly identify with the calling of the Jewish people, and that implies that you reckon yourself as worth saving... You must see yourself as the recipient of divine affection and love. After all, without this as a first step, how will you make the rest of the journey? This is similar to the First Commandment revealed at Sinai: “I AM the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt...” Notice that the statement, "I AM the LORD your God" (אנכי יהוה אלהיך) was uttered in the second person singular, rather than in the plural. In other words, you (personally) must be willing to accept the love of the LORD into your heart, since the rest of the Torah is merely commentary to this step of faith. Therefore the Book of Exodus is called Shemot (שְׁמוֹת), "names," because it sees every person as worthy of God’s redeeming love and revelation. “For God so loved the world...” (John 3:16).

The Midrash says that only one out of five of the children of Israel made it out of Egypt; some say one out of fifty, and some say one out of five hundred (see Mechilta). As Yeshua said: "Many are called, but few are chosen" (Matt. 22:14). Those who directly experienced God’s deliverance in Egypt first of all believed they were redeemable people. Before anything else they made a decision to receive hope within their hearts. The blood of the original Passover lamb was a smeared as sign of their faith that God would accept them. We also must begin here. This is the start of the journey. We step out by faith, leaving behind the familiar - including the dark familiarity of our sin and shame - and venture out into the unknown. We venture out in hope because we trust the promises of God (הַבְטָחוֹת יהוה).

The journey of faith (מַסָע הַאֱמוּנָה) is marked by testing (בְּדִיקַת אֱמוּנָה). Being called out of the world leads you into the desert places. Faith is not something static, like a church creed or theology handbook. There are stony places, dangers, and difficulties that attend the way. We move out from “walled cities” into tents, traveling as “strangers and sojourners” on our way to a promised heavenly city. Therefore the Scriptures state that "by faith Abraham went to live in the land of promise, as in a foreign land, living in tents with Isaac and Jacob, heirs with him of the same promise. For he was looking forward to the city that has foundations, whose designer and builder is God" (Heb. 11:9-10). The way back home is the same for all who "cross over" from this world to the next. It is the way of hope, trust, and surrender.

The story of divine deliverance is not the story of “other people”; it is not a story told in the “third person.” You must choose to belong. Again, your faith draws you near. That is why the sages teach: b'chol dor vador - in each and every generation an individual should look upon him or herself as if he or she (personally) had left Egypt. It's not enough to recall, in some abstract sense, the deliverance of the Jewish people in ancient Egypt, but each Jew is responsible to personally view Passover as a time to commemorate their own personal deliverance from the bondage of Pharaoh. The same must be said regarding Shavuot. Each person should consider himself as having personally received revelation at Sinai. The altar of the Mishkan was set up for you to draw near to God - you, not some people who lived long ago... This is why non-Jews who turn to the God of Israel by putting their trust in the Messiah are regarded equal members in the covenants and promises given to ethnic Israel. It is a brit milah (בְּרִית מִילָה) - literally, a "covenant of the word" - that makes us partakers of the covenantal blessings given to Abraham (Eph. 2:12-19; Gal. 3:7; Col. 2:11, etc.).

The narratives of the Book of Exodus, like other narratives of the Torah, often function as parables of faith (i.e., mishlei emunah: מִשְׁלֵי אֱמוּנָה). "The deeds of the fathers are signs for the children." Signs of what? Of the coming Messiah, as Yeshua Himself attested and the apostles likewise affirmed (John 5:46; Luke 24:27;44; Matt. 13:52; 2 Tim. 3:14-17). The Mishkan (i.e., “Tabernacle”) itself was a metaphor of God’s redemption (גְּאוּלַת יהוה) embodied in Yeshua. The Mercy Seat (kapporet) represented the Throne of God (Heb. 4:16; 2 Ki. 19:15) where propitiation for our sins was made (Rom. 3:25). Indeed, the word Mishkan (מִשְׁכָּן) is related to the word mashkon (מַשׁכּוֹן), a pledge or “promise on loan.” The Tabernacle functioned as a “loan” to Israel until the Messiah came to establish the true Temple (הַאֲמִיתִי הַמִּקְדַשׁ) by means of His atoning sacrifice (Gal. 3:19). The law (ספר הברית) is called a "schoolmaster" meant to lead to the Messiah and His Kingdom rule (Gal. 3:23-26). The glory of the Torah of Moses was destined to fade away (2 Cor. 3:3-11), just as its ritual center (i.e., the Tabernacle/Temple) was a shadow (צֵל הַמִצִיאוֹת) to be replaced by the greater priesthood of the Messiah (כְּהוּנָת הַמָּשִׁיחַ; see Heb. 10:1; 13:10). "Now we are released from the law, having died to that which held us captive, so that we serve in the new way of the Spirit (הַדֶּרֶך הַחֲדָשָׁה שֶׁל הָרוּחַ) and not in the old way of the written code (Rom. 7:6). Yeshua is the Goal of salvation (מְטָרָת הַיְשׁוּעָה) and the “Goel” (i.e., גּאֵל, Redeemer) from the curse of the law (קללת החוק)... "For the law made nothing perfect, but on the other hand, a better hope is introduced, and that is how we draw near to God" (Heb. 7:19). When the veil is taken away, Yeshua appears on every page of Scripture... (For more on this, see “Why then the Law?,” and “Paul’s Midrash of the Veil”).

Outside of the Mishkan, beyond the outer court, are the raw, “natural” experiences of life. This is the realm of the carnal flesh and the “dust to dust, ashes to ashes” despair of olam ha’mavet (עוֹלָם הַמָּוֶת). Genuine spiritual life (חיים רוחניים) is found when you come in through the gate (בְּדֶּרֶך הַשָׁעָר). You must understand that the gate is there for you to pass through.... The cross of Yeshua is the altar where He died for you, personally, for your atonement with the Father (מִזְבֵּחַ הַכָּפָּרָה). His blood was presented between the outstretched wings of the cherubim so that you could come before God “panim el panim,” that is, personally, “as a man speaks to his friend” (Heb. 4:16). Your faith bridges the gap between the Holy of Holies of the Cross (הַקֹדֶשׁ הַקֳּדָשִׁים שֶׁל הַצְּלָב) and the Sanctuary of your heart...

Isaiah 43:1

אַל־תִּירָא כִּי גְאַלְתִּיךָ

קָרָאתִי בְשִׁמְךָ לִי־אָתָּה

Isa. 43:1b Hebrew page (pdf)

Yes, i am Yours Holy EL SHADDAI. I just want to love and obey Him totally! How wonderful to be free to be all His by all He has accomplished for us! Thank you for this timely message dear Brother.

Thank you for this encouraging and uplifting message. Very rich meaning here. :)