"The paradox is the passion of thought, and the thinker without the paradox is like the lover without passion..." - Soren Kierkegaard

In a devar Torah (lesson) on parashat Vaetchanan, the late Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz summarized Moses’ farewell address to Israel as an extended appeal to flee from idolatry, which raises interesting questions about what idolatry really is. Before we delve into the topic, however, let’s recall the commandment against creating idols given at the Sinai revelation: “You shall have no other gods before me. You shall not make for yourself a carved image (i.e., pesel: פֶּסֶל), or any likeness (i.e., temunah: תְּמוּנָה) of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I, the LORD your God am a jealous God” (Exod. 20:3-4).

The French medieval commentator Rashi (1040-1105) noted that the Hebrew word “pesel,” translated here as “carved image,” comes from the root verb “pasal” (פָּסַל) meaning to carve or cut into shape, and therefore refers to chiseling, sculpting, or molding something into a particular figure from an earthly substance. By implication, a pesel refers to the effect of cutting, that is, a fragmentary or broken piece or outcome.... Some have said that the context of the prohibition regarding creating graven images constitutes a prohibition of use - a sober caution about how we are to relate to artwork in general... We are not to worship the creature rather than the creator (Rom. 1:25), mistaking the part for the whole, and this further implies we are not to worship the technology or skill of a particular artist.

The Hebrew word “temunah,” on the other hand, translated here as “likeness,” comes from the word “min” (מִין) referring to a “kind” or species, which sets apart the heavenly realm as a matter of human contrivance because Israel “saw no form when the LORD spoke at Horeb out of the midst of the fire” (Deut. 4:15). In short, the language of the Second Commandment seems to forbid making any concrete expression of the Divine Presence, a general prohibition against “finitizing” the infinite or identifying God with any aspect of creation (Psalm 145:3; 147:5; Isa. 55:8). In other words, while God sustains and upholds all things, He is is beyond all the "predications" of finite reality, and therefore we know him through a process of negation (via negativa), that is, by denying that the LORD can be categorized, identified, rationalized, explained, and so on. This is part of the meaning of the Name YHVH (יהוה) after all: the ineffable, unutterable mystery and wonder of the “in-finite” (אין סוף) divine presence (Gen. 32:29; Exod. 3:14; Judges 13:18; Isa. 9:6).

The sages say “Torah was written in the language of men,” and this raises interesting questions about the significance of religious language, how theological reference works, whether it is analogical or perhaps equivocal, as well as the use of metaphors, similes, and other figures of speech used in the Scriptures. It also touches on the “anthropomorphism” of God in the Bible, language describing God’s face, hands, arms, eyes, ears, and so on, as well as emotional expressions about God's anger, sorrow, pity, delight, and his great love for people.

Some Christian religious traditions have said that when Yeshua became a man at the time of the incarnation, God made himself into a finite representation and image among us, and because of this we are permitted the use of icons, hagiographic portraits, figurines and so on, as aids to worship. I think it is telling, however, that the New Testament does not describe the physical appearance of Yeshua other than in general terms, and therefore the argument that the incarnation “justifies” the use of religious icons or idols is suspect, especially if they are worshiped, venerated, or used as instruments of mediation in prayer...

Even if someone’s intentions are good, however, but they believe that representing God’s presence by means of symbolic forms or religious icons helps them to sense God’s presence, the Torah prohibition stands, for God alone is to be venerated and he is set apart from all of creation in his holiness. The pagan world sought to “reify” or bring down to earth the realm of the gods by means of icons and incantations, but this was not the way of God’s revelation to Israel given at Sinai. “You shall not bow down to them,” says the LORD, for I am the LORD your God, El Kanna (אֵל קַנָּא), a “jealous God” (Exod. 20:5). The sages have concluded that the worship of anything other than God is therefore a form of perfidy and idolatry.

But what about representations of heavenly things such as the Mishkan (Tabernacle) and its furnishings? What about the “cherubim” (כְּרוּבִים) that were forged upon the kapporet (cover) of the Ark of the Covenant? “Make one cherub (כְּרוּב) at one end, and the other cherub at the other end; you shall make the cherubim at the two ends of it of one piece with the cover of the Ark” (Exod. 25:19). Was Betzalel, the artist of the Ark of the Covenant, given an exemption against the prohibition to make “any likeness of anything in heaven”? What about the images of the cherubim on the parochet (veil) before the Holy of Holies?

These same sorts of representations were also permitted later in the construction of the Holy Temple. The Ark of the Covenant and the parochet used the same designs. Moreover, King Solomon made a copper basin (הַיָּם מוּצָק) that was upheld by twelve oxen that were positioned looking out in different directions (see 1 Kings 7:23-25). Apparently God did not object to the use of graven images of oxen there, but he judged Israel when Aaron made the image of the golden calf during the time of Sinai revelation.

The LORD has manifested his presence in ways human beings could understand. These are sometimes called “theophanies.” For instance, God spoke to Adam and Eve in the garden (Gen. 1:28); he called out to Noah and instructed him to build the ark at the time of the great flood (Gen. 6:13). Abraham heard God’s voice inviting to him to the promised land (Gen. 12:1) and he later encountered God in various visions (e.g., Gen. 14:18, Gen. 15:1, Gen. 17:15-22). The LORD also appeared to Isaac (Gen. 26:1-4), to Jacob (Gen. 35:1-7) and Joseph received visions of God’s deliverance to come (Gen. 37:1-11). Later Moses encountered God at the Burning Bush in the desert, and all Israel saw the thunderous display and heard the voice of God at Sinai. The Exodus generation saw the manifest glory of God (shekhinah) and heard God’s voice as they wandered in the desert. Later Joshua saw that Angel near Jericho (Josh. 5:13-15). Manoah and his wife encountered the Angel to announce the birth of Samson (Judges 13:1-23). The prophet Isaiah saw the LORD sitting upon a throne, high and lifted up (Isa. 6:1), as did the prophet Ezekiel (Ezek. 1:1). Elijah heard the “still small voice” of the LORD speaking to him (1 Kings 19:2) and Elisha saw the heavenly realm and the chariots of fire (2 Kings 6:17). Even the false prophet Balaam encountered God when he sought to curse Israel (Num. 22:31). There are severak other examples, of course, but this will suffice. “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets” (Heb. 1:1).

Let’s return to the Torah’s prohibition of idolatry. What makes some images of God permissible while others are forbidden? Steinsaltz says “If one adds a cherub, it becomes idolatry; if one removes a cherub, it becomes idolatry as well.” This reminds me of God’s warning to Moses regarding the construction of the Mishkan: “According to all that I show you, that is, the pattern of the Tabernacle and the pattern of all its furnishings, just so you shall make it” (Exod. 25:9). The “pattern” (i.e., tavnit: תַּבְנִית), was the plan or form that would reveal or correspond to divine truth. As you know, the “vision” of the altar at Sinai pointed to the cross of Yeshua, the Lamb of God, and therefore it served as a “parable” of what was to come. Just as every “jot and tittle” of the Torah was to be accounted for and fulfilled (Matt. 5:17-18), just one missing letter in a Torah scroll would make it pasul, or invalid. This is because Torah is whole, and does not allow exceptions or omissions, down to the very last word. Regarding the physical pattern of the Mishkan, the use of sacred images is permitted because they were embedded within a divinely sanctioned context...

A similar warning may be found when certain passages of the Scriptures are over-emphasized to the exclusion of other parts. Disregarding or suppressing passages of Scripture is to “remove a cherub,” to use Steinsaltz’s analogy. Of course there are “weightier matters” of Torah, but that has to do with the application and practice of faith, not the sanctity of the framework of Torah itself. Oversimplifying the meaning of the Scriptures by ignoring other Scriptures can lead to idolatrous practices and misunderstandings.

People want “soundbites” or quick answers to complexities, but we must be careful not to twist the Scriptures to fit accommodate our impatience. Paradox and ambiguities are part of the Scriptures. Some passages seem equivocal and even contradictory. This is not an accident but an intrinsic part of revelation itself. Shivim panim el Torah: “the Torah has seventy faces,” which means that multiple answers may be correct depending on the particular circumstances and context. For instance, Proverbs 26:4 says, “Do not answer a fool according to his folly (אַל־תַּעַן כְּסִיל כְּאִוַּלְתּוֹ) lest you also be like him,” while the very next verse says “Answer a fool according to his folly (עֲנֵה כְסִיל כְּאִוַּלְתּוֹ), lest he be wise in his own eyes” (Prov. 26:5). To answer or not depends on the circumstances.

How can God “repent” of a judgment when it is said that he is not like a man who changes his mind? (Gen. 6:6; Exod. 32:14; Num. 23:19; 1 Sam. 15:29; Isa. 49:11). “The counsel of the LORD stands forever; the plans of his heart to all generations” (Psalm 31:11). Why did God forbid the use of graven images but instructed Moses to male a bronze serpent in the desert (Num. 21:8)? Why does the Torah says God spoke to Moses “face to face” (Exod. 33:11) and then God is quoted just a few verses later saying no one could see his face and live (Exod. 33:20)? Likewise the Apostle John said that “no one has seen God at any time” (John 1:18) yet Yeshua said that whoever had seen him had seen God (John 14:7-10). Indeed the prologue of the Gospel of John reads: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made by Him, and without Him nothing was made that was made... And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we have seen His glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth” (John 1:3, 14). There it is. “No one can see my face and live” and yet “blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.” At Peniel Jacob said, ‘I have seen God face to face, and yet my life has been delivered” (Gen. 32:20), and the 70 elders of Israel ate a covenant meal at Sinai where they “saw the God of Israel. And there was under His feet as it were a paved work of sapphire stone, and it was like the very heavens in its clarity” (Exod. 24:10), Isaiah beheld the LORD in his throne room and yet the Lord "dwells in unapproachable light, whom no one has ever seen or can see" (1 Tim. 6:17).

I am not trying to be provocative here, much less skeptical about the possibility of being able to discern and receive the truth of God as revealed in Scripture, but we need to be aware of these sorts paradoxical tensions and challenges as our faith seeks understanding. Just as God allows heresies within the church to authenticate those of true faith (1 Cor. 11:19), so we must be tested to believe before we are able understand (John 13:17). The paradoxes are part of the revelation, the whole counsel of God. “The whole commandment (כָּל־הַמִּצְוָה) that I command you today you shall observe and do, that you may live” (Deut. 8:1). The complexity of the issue may be found in the parallel yet antipathetic commandments to both love and to fear the Lord your God (Deut. 6:5; Deut. 6:13). These ideas are put together in the verse: “You shall walk after the LORD your God, and fear him, and keep his commandments, and obey his voice, and ye shall serve him, and cleave to him” (Deut. 13:4). The fear of God appears in the midst of the whirlwind and our hearts draw back in awe, but the love of God appears in his great compassion for us, and our hearts seek to draw close. We experience love’s fear and trembling, holy desire mixed with dreadful awe. Both ideas are important and essential, even if together they present a tension.

It’s been said that if you take hold of a tzitzit (tassel) of Messiah, you take hold of him, but if you only take hold of a tzitzit, you are left holding a tatter. If you take hold of God’s word, you will take hold of it all, including the paradoxes, tensions, and obscurities, but if you read only what you are looking for, you will be left with glittering generalities that will not stand the test of truth. Despite the anxiety of not fully understanding, we must refuse generalizations and ad hoc explanations intended to deny the struggle and to make our theology “agreeable” for us.

We are faced with many paradoxes that stress “understanding” our faith. The Infinite becomes the finite; the Holy One becomes sin for us; by his stripes we are healed; God is utterly transcendent yet entirely immanent; God is sovereign and decrees the beginning from the end, yet each soul is bound by time and will face judgment for their free choices; God made everything “very good” yet there was a snake loose in the garden to tempt Eve, and so on. We struggle and fail and yet we are beloved. There are times of great hope yet dark passages in the journey of faith. We are to love God “be’khol levavkha” with all our heart, but that heart must accomodate our joys and sorrows, our insights and darkness, the way of ascent and of descent. We stand in awe before God and sigh from the depths of our need for unconditional love...

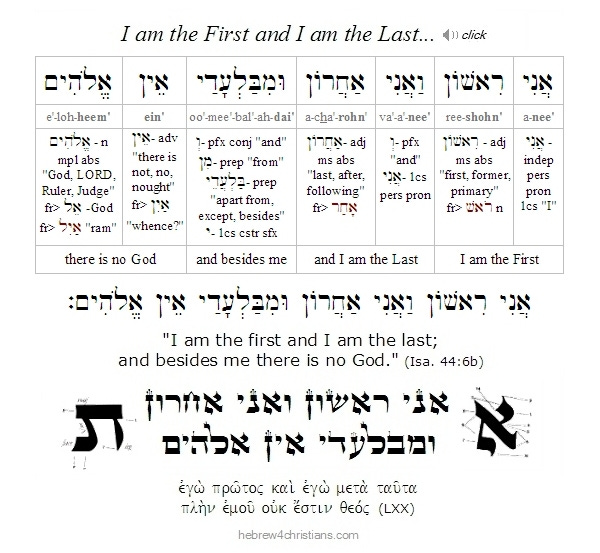

Isaiah 44:6b

אֲנִי רִאשׁוֹן וַאֲנִי אַחֲרוֹן

וּמִבַּלְעָדַי אֵין אֱלֹהִים

"I am the first and I am the last;

and besides me there is no God."

Thank you for this thought provoking post. I found myself, unintentionally, reading two essays last week on the subject of Paradox. Since then I have been trying to make a reply or response here and haven't been able to put it to words adequately. The Kierkegaard quote helps, as do these from Fr. Benoit Standaert, OSB in his book Spirituality: an Art of Living, "Paradoxes are essential. They add irrationality to even the wisest life philosophies" and "Thanks to paradox, we learn we can lift up common opposites and find new perception of reality." John Keats coined a phrase "negative capability" with regard to writing/art making. "...what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, especially in Literature, and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason—"

Perhaps It's like the totalitarian approach with certainties wrapped up in a neat totalitarian package to obtain collective agreement without argument; or the Free Will approach of seeing how opposites or opposing facts can actually somehow be agreeable, which requires individual thought, effort and creativity. This next quote from Keats is inspiring to me as a painter and bible reader/believer who has actually worried about the commandment to not make graven images... "We hate poetry that has a palpable design upon us—and if we do not agree, seems to put its hand in its breeches pocket. Poetry should be great and unobtrusive, a thing which enters into one's soul, and does not startle it or amaze it with itself but with its subject"

Please pray for me. Living in a rooming house where the other people are anti semitic. Also the owner/ landlord just sold the house so I have until months end to find another place. Thank you