When R’ Bunam was lying on his deathbed, his wife wept bitterly. Thereupon he said, “Why are you weeping? All my life has been given me merely that I might learn to die.”

Shalom chaverim. Recently we read about Abraham’s greatest trial of faith when God asked him to take his promised son and sacrifice him as a burnt offering. How are we to understand this test, and what might we learn from it? Abraham’s obedience is a central lesson of course, and his willingness to sacrifice his son demonstrated his faith in God. But this willingness reveals the utmost level of surrender, a “faithful crucifixion” of his life that bore witness to the coming Lamb of God who would be sacrificed to bring healing for the whole world.

The story of Abraham’s “walk of faith” is one of testing and great perseverence. Though he had heard God’s call to “lekh-lekha” (לךְ־לְך), “to go” to an unseen land of promise and blessing, there were many troubles along the way. After he made the long journey from Ur of the Chaldees and came to the land as directed by God, he immediately encountered a severe famine which forced him leave the land and go to Egypt in search of food. While in Egypt his wife Sarah was abducted into the Pharaoh’s harem to be a concubine. After God plagued the king’s house and warned him to “let my people go,” the Pharaoh hastily summoned Abraham and told to take his wife and go back to the promised land (prefiguring the later Exodus from Egypt under Moses). When Abraham and Sarah returned to the land of Canaan, his nephew Lot separated from them and moved to the Plain of Jordan, near Sodom and Gomorrah, to find more pastureland for his growing cattle and herds. Some time later a war broke out in the Plain and Lot and his family were taken captive by the conquering kings of the area. Abraham marshaled his clan and rescued his nephew from captivity. After this he was met by the mysterious “Malki-Tzedek,” the king and priest of Shalem, who brought out bread and wine and blessed Abraham in the name of the Most High God, the Possessor of heaven and earth (אֵל עֶלְיוֹן קֹנֵה שָׁמַיִם וָאָרֶץ).

Some time later God appeared to Abraham in a vision to reaffirm his original promise to make him into a great nation. After showing him the vast sweep of the stars in the night sky, God said “so shall your offspring be.” Despite his years of apparently fruitless wandering, Abraham believed God and God accounted his faith as righteousness (Gen. 15:6). The LORD then renamed Abram, meaning ”exalted father” to Abraham. meaning “father of a multitude.” He also renamed Sarai (meaning “princess”) to Sarah, appending the letter Hey (ה) to indicate his blessing and presence. God then made covenant with Abraham to inherit the land of Canaan forever; Abraham was 75 years old when he had this vision.

After he had lived in the land of Canaan for some time, Abraham began to wonder how God’s promise to make of him a great nation would be realized. The years were passing by and he and Sarah remained childless. Perhaps Eliezer of Damascus, his chief servant, was to be his heir? Sarah, also eager for a child, decided to take matters into her own hands and ordered her servant Hagar, given to her by the Pharaoh in Egypt to be his concubine. Hagar became pregnant but Sarah soon became jealous. She treated Hagar so harshly that she ran away but later returned after she was met by an Angel who promised that her child would also become a great nation. Abraham was 86 years old when Ishmael was born (Gen. 16:1-16).

Nearly 25 years after the vision of the stars, when he was 99 years old, God again appeared to Abraham using the name El Shaddai (אֵל שַׁדַּי), “the All-Sufficient One,” and reaffirmed his promise that he would be the father of a multitude of peoples (Gen. 17). Soon after this revelation Abraham was visited by the three angels, one of whom was the Angel of the LORD himself, who told Abraham that Sarah would indeed have a son within a year. Sarah laughed at the announcement, but the LORD affirmed his words (Gen. 18:1-15). The other two angels then left to go to Sodom, to determine whether it would be condemned to judgment, while Abraham spoke with the Angel of the LORD and interceded on behalf of the city. Nevertheless Sodom and its surrounding area was destroyed by fire and brimstone, though Lot and his daughters escaped (Gen. 18:16-19:20).

When Abraham was 100 years old, Sarah indeed gave birth to a son! They called his name “Isaac” (i.e., Yitzchak) as directed by the Lord (Gen. 17:9), a name which means “he laughs”– and a play on words that expressed the great joy of Abraham and Sarah over the miracle of their son (Gen. 21:1-7). Abraham circumcised his son when he was eight days old, as God had commanded (Gen. 17:10). After Yitzchak was weaned, however, Sarah demanded that her servant Hagar and her son be removed from the family so that there would be no controversy about who the promised heir of Abraham truly was. In sorrow Abraham sent them away, though God told him that Ishamael would survive and become a great nation. The LORD reaffirmed to Abraham, however, that Yitzchak was indeed the chosen heir through whom his descendants would come. “In Isaac your seed shall be called...” (Gen. 21:12).

The Torah is silent about the early years of Isaac, but many years later, when Abraham was 137 years old (and therefore Isaac was 36), he faced his greatest trial of faith when God asked him to sacrifice Isaac as a burnt offering on a mountain... Wait, what? Is this for real? After all his years of hope and struggle, would it all come down to this: the sacrifice of his beloved son? a “whole burnt offering” of his dreams, the holocaust of his vision?

And what about Isaac? When was he asked to become the sacrificial victim? Did he understand what was being asked? Did he have some earlier premonition? He was no longer a child but a grown man. Abraham needed Isaac to agree to become the sacrificial victim, but how could he explain all this to him without sounding insane? Apparently he did not object, though it must have greatly alarmed him. This test was not just for Abraham but for his son Isaac, too, and it was to Isaac’s great credit that he willingly submitted to the request of his father to die on his behalf...

Perhaps you are tempted to think all this was a “charade” of sorts? That Abraham knew all along that Isaac wouldn’t die, that God wouldn’t allow this to really happen, and therefore he went along with just to play his part in the macabre drama? But there is no such indication given in the Torah. God’s instructions were clear enough and unambiguous. Abraham would sacrifice, that is, slaughter his son upon an altar and then burn his body as a whole burnt offering. I do not think it was meant to be a “prophetic parable,” because what sort of a test would that be? What sort of sacrifice? For his part, Abraham was ready to do God’s will, no matter what was asked of him. Indeed the very next morning after God asked him to sacrifice his son Isaac, Abraham saddled his donkey and got things ready for the offering (Gen. 22:1-3).

Recall that the first “lekh-lekha” (לךְ־לְך) was a call to go to the “promised land” of God: “Go from your homeland (מֵאַרְצְךָ), and from your kindred (וּמִמּוֹלַדְתְּךָ), and from the house of your father (וּמִבֵּית אָבִיךָ), to a land that I will show you” (Gen. 12:1), and the second “lekh-lekha” was a call to go and annihilate the vision the promise of becoming the father of the nation: “Please take your son (קַח־נָא אֶת־בִּנְךָ), your chosen son (אֶת־יְחִידְךָ), whom you love (אֲשֶׁר־אָהַבְתָּ), namely Isaac (אֶת־יִצְחָק), and go to the land of Moriah (וְלֶךְ־לְךָ אֶל־אֶרֶץ הַמֹּרִיָּה) and offer him there as a burnt offering (לְעֹלָה) upon one of the mountains which I will show you” (Gen. 22:2). Go away from all you were - your history, your birthplace, your father’s house ... and come to the place that transcends all that is natural and of this world, a place of resurrection and the world to come. In both cases there is a call to the unknown and the test to believe that God would lead him to the place of blessing, despite everything he faced (Gen. 12:2, Gen. 22:17). In the climactic test, however, God showed Abraham the cross of Messiah, the place where his Son would be bound and offered as a sacrifice for the healing of the nations. It reveals the heart of the Father who would give up everything, including his beloved Son, so that we may have eternal life.

According to the author of the Book of Hebrews in the New Testament, Abraham believed that God would raise Isaac from the dead after he completed the sacrifice: “By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises offered up his only begotten son, of whom it was said, ‘Through Isaac shall your offspring be called.’ He considered that God was able even to raise him from the dead, from which, figuratively speaking, he did receive him back” (Heb. 11:17-19). Imagine Abraham binding Isaac’s arms and feet while saying, “After the sacrifice, I will see you again: you will be brought back to life!” No matter how we may try to rationalize this, it is clear that Abraham accepted God’s will - even if what was asked seemed terrifyingly preposterous, even insane...

They followed the cloud. After three days they reached the mountain, the place of the sacrifice. They left the others behind as they began their ascent. Isaac carried the wood that would burn his body. Abraham carried the knife and the torch. Together they built an altar of stones and arranged the wood for the fire. Abraham then asked Isaac to lay himself down on the altar as he bound the hands and feet of his son.

As Abraham silently looked upon the knife, all of his history, his hope, and his struggle was refracted back in the glint of the blade’s edge. Was he willing to go through with this? Even if God would bring Isaac back from the dead, would he be able to plunge the knife into the heart of his promised child, the heir of his life? He steeled his resolve and carefully lifted the knife above his waiting son. Their eyes met and both took a deep breath just as Abraham was about to thrust the knife down. At the very last instant, the Angel spoke: “Abraham! Abraham! Do not lay your hand on the lad, or do anything to him; for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from me” (Gen. 21:11-12).

After a moment of utter shock, Isaac was released, unbound from death, and raised up to new life. For the Angel testified before heaven and earth that the sacrificial act was was “fait accompli,” an accomplished fact, and that Abraham had indeed offered up his only begotten son who had been raised from the dead. It was just then that Abraham saw the “ram caught in the thicket” that was to be sacrificed in Isaac’s place. But why a ram instead of a lamb? Because when Abraham had said, “God will provide for himself a lamb” (אֱלֹהִים יִרְאֶה־לּוֹ הַשֶּׂה) this referred to the coming of Yeshua, the great Lamb of God, but the ram was provided for Abraham in place of Isaac for the sacrifice. The ram was not the lamb that God would provide “for himself” to atone for the sins of the world and reconcile his justice with his love, but rather a sacrificial ram that was provided for Abraham in place of Isaac. This seems to be the right understanding since later Abraham called the place of the altar at Moriah “Adonai Yireh” (יְהוָה יִרְאֶה), in reference to the Lamb God to come who was to be provided by God himself in fulfillment of the prophecy (Gen. 22:8, Gen. 22:14).

The ashes of the sacrificed ram represented the dust and ashes of Isaac, and of Abraham as well. The “ashes of Yeshua” came from his passion upon the cross, and represent the atonement and exchange he made for the resurrection from the dead. God did indeed provide the Lamb - Adonai yireh ha’seh - and we will see this when we “ascend to the mountain” (Gen. 22:14). Yeshua later told the rabbis of his day, “Abraham rejoiced to see my day: and he saw it, and was glad.” When they objected by saying that he was too young to ever have seen Abraham, Yeshua answered: “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I AM,” which provoked them to try to stone him for blasphemy (see John 8:56-59).

Allow me now to consider whether Abraham might have been traumatized by the (near) sacrifice of his son. The sages say that when Sarah later understood what had happened, her heart gave out and she died. And Abraham’s relationship with Isaac may also have been fractured as well. Did Isaac hear the voice of the Angel? The Torah does not indicate that he did. Perhaps Isaac was also deeply traumatized by the ordeal and needed some time apart from his father. Later on, after Abraham commissioned his chief servant Eliezer of Damascus to find a bride for his son, there is no recorded dialog between the father and son, and while Abraham bequeathed everything he had to Isaac, the last time Isaac saw his father was at Abraham’s burial at Machpelah (Gen. 25:9). At any rate, the sacrifice at Moriah must have haunted Abraham during his remaining days, yet he pressed on in faith, later remarrying and having other children. Like the story of Job, from the whirlwind God’s blessing will come...

Recall at the outset of this article that I had wondered whether Abraham might have been tempted to protest God’s will for life, and that leads to the related question of whether you have ever found yourself protesting the course of your life and inwardly wrestling to accept God’s will... Do you struggle with the call to “take up the cross” as did Abraham - and follow Yeshua?

How much do you “need” to understand before you are willing to let go and surrender? Do you put God in the test - subconsciously demanding that he justify himself to you before you will obey? How did Abraham find the paradoxical strength to die to himself? How do we?

So much is beyond our control and we understand so little. We can either abhor all that happens that we cannot understand, or we can trust that God has a plan that, although inscrutable to us and sometimes seemingly cruel, is nevertheless the ordained way of our lives. Yes, “ordained,” for nothing happens in our lives due to “random” forces or by chance, for the LORD God Almighty knows the beginning from the end, and all of reality is His story to tell. God is the Central Character of the thing called “life,” and indeed He is the creative force and Author of all that exists. Faith believes that the story is about his vindication of love despite all the darkness, evil and shame that seeks to deny its fulfillment.

Reinhold Niebuhr’s well known “Serenity Prayer” expresses the balance we need to walk in the present ambiguity and “already-not-yet” fulfillment of God’s story. It begins, “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change.” That’s most things of life. Nearly everything. “Who among you by being anxious can add a single hour to his span of life?” “Serenity,” or inner peace (שָׁלְוָוה פְּנִימִית), first comes from “acceptance” (קַבָּלָה), that is, receiving whatever is the case (קבלה של הכל), and not fighting it, not lamenting over it, not negotiating with it - just willingly accepting it as something God has allowed. “Thy will be done.” Whatever bothers us is likely out of our hands anyway, and it is tragically foolish to “play God” in any circumstance.

“God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” yes, that makes sense, but the prayer continues, “and [grant me] the courage to change the things I can.” Though many things are indeed beyond our control, such as who our parents and ancestors were, when and where we were born, the state of the world we inhabit, and so on, some things are not. There are genuine choices we must make in life for which we are responsible and from which we cannot abstain. “Ought implies can” which means there is a moral order to reality and that we have the ability to make meaningful choices. We are born with a conscience; we have intuitive awareness of right and wrong, of good and evil. Choosing not to chose is itself a choice; saying you “can’t help it” and making excuses by blaming circumstances is “bad faith.” To decide means to “cut away” other options, and that requires courage because we don’t know the effect of our choices with certainty. We are nevertheless accountable for whatever we choose, and our judgments and reasons that justify our choices imply that we are responsible for how we think, for our attitudes, our values, and so on. Faith provides the courage to trust in the unseen good rather than to allow fear to devour our souls.

“Faith is nothing else but a right understanding of our being - trusting and allowing things to be; a right understanding that we are in God and God whom we do not see is in us.” — Julian of Norwich

The Serenity Prayer ends with the phrase, “and [grant me] the wisdom to know the difference.” This is very practical. Some things you can’t change and must accept; other things you can change and must choose. Wisdom is understanding what’s in your power and what’s not, and therefore knowing what you must accept (for the sake of inner peace) and what you must actively fight (for the sake of duties of your heart). Acceptance is based on necessity whereas courage is based on possibility; knowing the difference is wisdom.

Surely it takes wisdom to relate to God - for that is what we are talking about, really - how to find peace by surrendering to his will, and how to find courage to take responsibility for whatever you decide to do. The life of faith is not easy and tests are inevitable. God designed it that way and we must accept that. Yet we must choose to keep hope alive despite our finitude, brokenness, and inability to fathom much of anything. At times we will experience respite and calm; at other times we will struggle and fight. Either way we need wisdom. As Job said Adonai natan, v'Adonai lakach: yehi shem Adonai me'vorakh: “The LORD has given, the LORD has taken away; let the name of the LORD be praised” (Job 1:22). Whatever happens, however, we call out to God for his blessing and help. We seek His face. We will not give up, even if we don’t understand. And that is the Torah of Abraham, who courageously accepted everything and was set free by choosing to believe in the truth of God’s love.

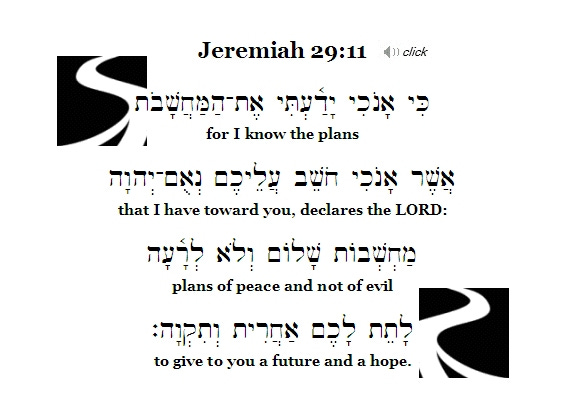

Jeremiah 29:11

כִּי אָנֹכִי יָדַ֫עְתִּי אֶת־הַמַּחֲשָׁבֹת

אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי חֹשֵׁב עֲלֵיכֶם נְאֻם־יְהוָה

מַחְשְׁבוֹת שָׁלוֹם וְלֹא לְרָ֫עָה

לָתֵת לָכֶם אַחֲרִית וְתִקְוָה׃

“For I know the plans

I have for you, says the LORD:

plans for peace and not for evil,

to give you a future and a hope.”

Jeremiah 29:11 Hebrew page (pdf)

https://hebrew4christians.com

Praise YHVH for our leaders and elders who teaches us the truth in courage and strength. May our faith remain unwavering till Yeshua 's return. Blessings 🙌 to my family. Shalom

Excellent. I truly appreciate your work…

Thank you. 🤍