Since this week we are reading about the giving of the law at Mount Sinai, I think it's fitting to revisit the question of what the Torah is. Does the word simply refer to the tablets with the Ten Commandments inscribed on them, or perhaps to the written scrolls that contained the collected writings of Moses? If the latter, then by whom and by what process were these writings ratified as divinely inspired Scripture? And does this ratification imply that the idea of “Torah” includes “oral” traditions that have identified, discussed, interpreted, and applied the meaning of the written words for every generation? If so, does “oral” Torah have the same authority as the written words of Moses (and by extension, the words of the prophets)? In short, how are we to understand what the Torah is and how we are to apply it to our lives?

In order to answer some of these questions, we need to dig a bit deeper. As many of you know, the Hebrew word Torah (תּוֹרָה) comes from the root word yarah (יָרָה) meaning “to shoot an arrow” or “to hit the mark.” When used in relation to moral and spiritual truth, the word means “direction” or “instruction” regarding doing the will of God. Practically speaking, however, Torah refers to the apprehension of divine wisdom (חָכְמָה), that is, upright thinking and doing as directed by divine imperatives (mitzvot: מִצְווֹת) revealed in the holy Scriptures and practiced through sanctified discipline (mussar: מוּסָר). In other words, "Torah" is related to the idea of commandments, or the imperatives given by God.

The sages note that are two basic categories of commandments: mitzvot aseh (מִצְוֹת עֲשֵׂה), or positive directives ("thou shalt..."), and mitzvot lo ta'aseh (מִצְוֹת לא תַעֲשֵׂה), or negative directives ("thou shalt not..."). A positive commandment is obligation to do something, whereas a negative commandment is an obligation to refrain from doing something.

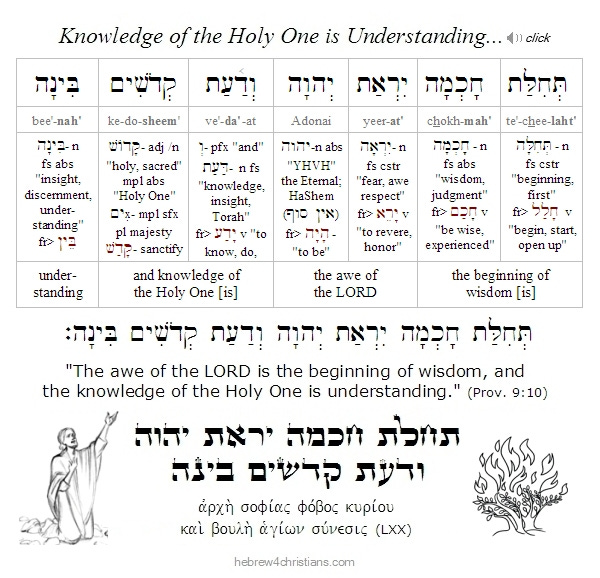

The Jewish Scriptures are filled with directives intended to awaken us to the reality of God’s immanent Presence. “Da lifnei mi attah omed” (דַּע לִפְנֵי מִי אַתָּה עוֹמֵד) - “Know before Whom you stand.” There are 613 commandments given in the Torah of Moses, hundreds more found in the Writings (הַכְּתוּבִים) and the Prophets (הַנְּבִיאִים), and over a thousand revealed in the New Testament (הַבְּרִית הַחֲדָשָׁה). All of these imperatives are intended to give voice to the concern and love of God by pointing to the blessing of knowing the Divine Presence in the midst of our daily lives. Torah teaches us to make choices according to the divine light revealed in Scripture. Godly wisdom is grounded in the fear (i.e., respect) for the gift of life that will be expressed through the discernment between the sacred and the profane, good and evil, right and wrong, in our daily lives. This is called yirat shamayim (יראת שמים).

“All of these imperatives are intended to give voice to the concern and love of God by pointing to the blessing of knowing the Divine Presence in the midst of our daily lives.”

Proverbs 9:10

תְּחִלַּת חָכְמָה יִרְאַת יְהוָה

וְדַעַת קְדֹשִׁים בִּינָה

“The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom,

and the knowledge of the Holy One is understanding.”

In Jewish thought, the word “Torah” (תּוֹרָה) is therefore a general term that implies a wide range of related ideas and concepts that focus on discerning God’s will. A primary distinction is between the written Torah, on the one hand, and the oral Torah on the other. The written Torah, called she’bichtav (שֶׁבִּכְתָב, “that which is written”), refers to the text that has been meticulously transmitted since the time of Moses in the form of a Sefer Torah (i.e., a kosher Torah scroll). The oral Torah, on the other hand, is called shebal peh (שֶׁבְּעַל פֶּה, "that which is oral"), and refers to legal and interpretative traditions handed down by word of mouth until these were codified in the Mishnah and Gemara (i.e., the Talmud). The Oral tradition further includes the Midrash (traditional exegesis), the Responsa (questions and answers given by “poskim,” or legal scholars), the Shulchan Aruch (16th century codification of Jewish case law), and various other commentaries handed down over the centuries. Some people also say that Kabbalah (קַבָּלָה), or the text of the Zohar (זֹהַר), is also oral tradition, though strictly speaking it is not regarded as part of the Oral Torah as understood in Jewish tradition.

Jewish thought or “hashkafah” (השקפה) further maintains that the written Torah and the oral Torah are complementary, since Moses himself (inspired by Yitro) established the role of judges and law courts as part of the written Torah from the very beginning (see Exod. 18:13-26; Num. 11:24-29; Deut. 16:18-20; 17:8-12), and ultimately the oral Torah derives its justification and substance from the written revelation. Indeed it is somewhat artificial to distinguish between the two in practice, since the written Torah was preserved through tradition (i.e., the scribal transmission, the books to be included in the canon, etc.), just as the oral Torah was validated by the written words of the Torah scroll itself.

Moreover, within both of these “Torahs” we can make further distinctions. For example, in the written Torah there is both narrative (עלילה) and Gods’ explicit commandments (מִצְווֹת), which roughly corresponds to the distinction between homiletical (אגדי, “aggadic”) and legal (הלכתית,“halakhic”) literature found in the oral Torah. In addition, just as the 613 mitzvot of the written Torah can be subdivided into the categories of laws or rules (i.e., mishpatim: משפטים), decrees (i.e., chukkot: חוקים), and testimonials (i.e., eidot: עֵדֹת), so the Jewish legal tradition discusses the corresponding ideas of case laws (i.e., takkanot: תקנות), rabbinical decrees (i.e., gezerot: גזרות), and customs (i.e., minhagim: מִנְהָגִים).

In short, there is a sort of “circular reasoning” involved in the traditional Jewish idea of Torah: The written Torah was passed down (validated) by means of the oral Torah; but the oral Torah derives its authority from the written Torah:

It should be noted that this same sort of interplay between interpretation (i.e., theology) and the written Scriptures appears in the Christian tradition as well…

Interestingly enough, Jewish tradition seems to go two ways with the idea that Torah can be explicated by means of halakhah. On the one hand, it carefully enumerates every nuance of each of the various commandments of the Torah, creates various takkanot (case laws) and even multiplies the Torah’s principles by building “fences” (gezerot) around the commandments, yet on the other hand it can (and does) distill the various commandments of the written Torah to more general principles that are fewer and fewer in number. For example, in Makkot 23b-24a the discussion goes from an enumeration of the 613 commandments identified in the Torah, to David’s reduction of the number to 11 (Psalm 15), to Isaiah’s reduction of the number to six (Isaiah 33:15-16); to Micah’s reduction to three (Micah 6:8); to Isaiah’s further reduction to two (Isaiah 56:1); ultimately leading to the one essential commandment spoken by the prophet Habakkuk (“The righteous shall live by his faith” - Habakkuk 2:4). Obviously the Apostle Paul distilled the various mitzvot to this selfsame principle of faith (see Rom. 1:17, Gal. 3:11, Heb. 10:38).

Now Yeshua was "the Voice of the Living God (קוֹל אֱלהִים חַיִּים) speaking (davar) from the midst of the fire" at Sinai (Deut. 5:26), and therefore He is the Divine Lawgiver (מְחוֹקֵק) of mankind. As the Ruler of Israel (ריבון ישראל), Yeshua reiterated and amplified the axioms of the Ten Commandments (עשרת הדיברות) in the Sermon on the Mount, emphasizing that they were not merely external rules of conduct but matters of the heart... In this connection is important to make the distinction between the general idea of Torah (תּוֹרָה) with the more specific idea of covenant (בְּרִית), since these are different (though related) things.

While the Hebrew word “Torah” means “instruction” or "teaching," the word “covenant” refers a specific agreement or "contract" made between God and man. In order to avoid potential confusion between the Torah of Moses (תּוֹרַת משֶׁה) and the Torah of Yeshua (תּוֹרַת הַמָּשִׁיחַ), then, we must keep in mind that Torah is always a function of the underlying covenant of which it is part. This implies that if the covenant were to change, so would our responsibility (i.e., Torah). As it is written in the New Testament: "For when there is a change (μετατιθεμένης) in the priesthood, there is necessarily a change in the law as well" (Heb. 7:12). Now the word translated "change" in this verse comes from the verb μετατίθημι (from meta, "after" + tithemi, to "set") which might better be translated as "transposed." The idea is the priesthood reverted to the original Malki-Tzedek priesthood of Zion and therefore required a corresponding "transfer" of authority (μετάθεσις) to the original kingship as well. Yeshua alone is both High Priest and King... The failure to make this distinction leads to exegetical errors and invalid doctrines. We must “rightly divide” (ὀρθοτομέω, lit. “cut straight”) the “word of truth” (דְּבַר הָאֱמֶת, see 2 Tim. 2:15).

In light of this you will then realize that the general sense of "Torah" predated the giving of the law at Sinai (מתן תורה), since the divine wisdom was passed down from Adam and Eve through the godly line of Seth to Noah, then through Noah's son Shem and his line through Eber unto the advent of Terach and his son Abraham. Of Abraham it was said that he observed the divine wisdom of Torah some 400 years before the revelation at Sinai: "Abraham... kept my charge, my commandments, my statutes, and my Torah" (Gen. 26:5). Moses, too, kept the Torah before Sinai. For instance Moses offered the Passover sacrifice in Egypt, before God had formally proclaimed the laws for sacrifice at Sinai. Later the Passover sacrifice of the Lamb of God was enshrined as the consummate sacrifice, offered every evening and morning (קָרְבַּן תָּמִיד) to commemorate the redemption by means of blood atonement. Moses further ratified the Sinai Covenant with blood from sacrificed bulls, though this again was not authorized by the written Torah, of course. Other sacrifices were given to reinforce the principle of "life-for-life" exchange, originally prefigured by the sacrifice of Isaac (i.e., the Akedah).

The early sages further understood there to be different levels of Torah even after the revelation at Sinai. First there was the oral component to the written law of the Sinai covenant (i.e., sefer ha'brit: ספר הברית) that elaborated and explained the moral and ritual obligations for Israel. We see this in the system of judges (שופטים) and religious court system (בְּתֵי דִּין) that developed case law, for example. Consider also the elaborate rules developed to ensure accuracy in the preservation of the manuscripts of the Torah, or consider the scribal traditions that defined (and retained) the meaning of Hebrew words, the punctuation, vocalization, and reading style (i.e., nusach: נוסח) the Hebrew text, and that further ordered and attested authentic manuscripts, and so on.

As I've mentioned before, the written Torah did not come with a dictionary, so people had to learn the meaning of words, how to understand grammatical constructions, and how to vocalize the texts by means of teaching that spontaneously accompanied the revelation at Sinai. Moreover, not everything is written down, and what is written required authority in matters of interpretation. For example, consider the various details required to construct the “Tabernacle” (i.e., mishkan: המשכן) that were not explicity stated in the written Torah. So the written Torah was always in dialectical relationship with the interpretation and teaching of the leaders and judges of Israel, and later this "dialog" included messages from appointed Hebrew prophets (נביאים עבריים) who foretold the vision of Zion and the advent of the Messiah. The sages had long said that the Torah of Moses was covered with a veil obscuring the true light, which would be lifted beginning with the promised Days of Messiah (ימי המשיח).

Traditional Jewish eschatology understands human history to be divided into three epochs of two thousand years each. From Adam until Noah is called "tohu" (תּהוּ); from Abraham until Messiah is called "law" (חוק); and from Messiah until the End of Days (אחרית הימים) are the days of Messiah (ימי המשיח). Note that this division of history explains why the Jewish people had such fervent Messianic expectation during the time of Yeshua, some 2,000 years ago. After the End of Days the Messiah will establish the kingdom of Zion (מַלְכוּת ציון) upon the earth for a thousand year epoch, regarded as the Sabbath of history (השבת של הדורות) and the fulfillment of the promises given to Israel through the Hebrew prophets.

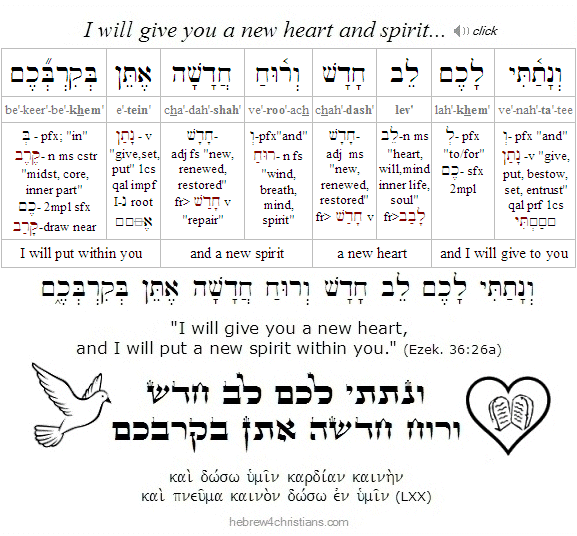

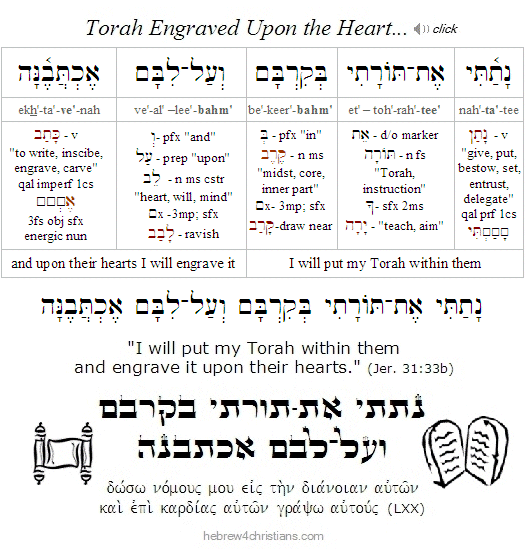

One implication of this overarching paradigm is that the idea of "Torah" is subject to change, since God gave additional (though complementary) ways of connecting with him based on his covenantal actions in history. For example, even though the new covenant does not nullify Torah, it transcends the terms of the Sinai covenant with its terms of blessings and curses (i.e., tochechah: תוכחה). Yeshua is the "goal" of "end" of the Torah given at Sinai, not in the sense of its repudiation but in the sense of its consummation, that is, the "Torah written upon a new heart (i.e., lev chadash: לב חדש) and a new spirit (i.e., ruach chadashah: רוח חדשה) that partakes of the divine life of Messiah and his righteousness (Jer. 31:31-33; Ezek. 26:26).

Ezekiel 36:26a

וְנָתַתִּי לָכֶם לֵב חָדָשׁ

וְרוּחַ חֲדָשָׁה אֶתֵּן בְּקִרְבְּכֶם

“And I will give you a new heart,

and I will put a new spirit within you.”

Ezek. 36:26b Hebrew page (pdf)

Jeremiah 31:33b

נָתַתִּי אֶת־תּוֹרָתִי בְּקִרְבָּם

וְעַל־לִבָּם אֶכְתֲּבֶנָּה

Jer. 31:33b Hebrew page (pdf)

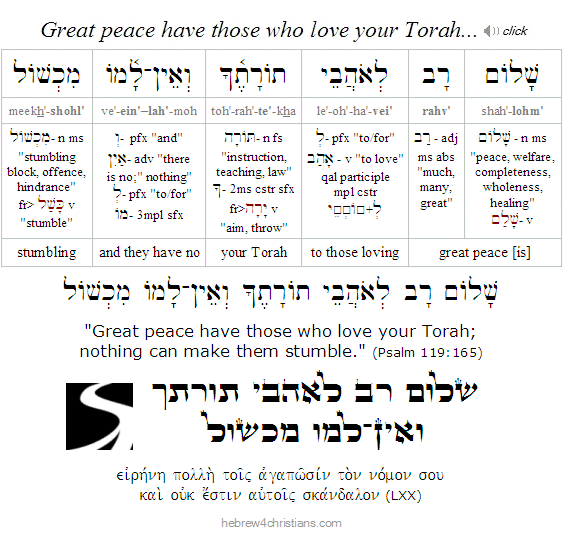

Psalm 119:165

שָׁלוֹם רָב לְאֹהֲבֵי תוֹרָתֶךָ

וְאֵין־לָמוֹ מִכְשׁוֹל

Psalm 119:165 Hebrew page (pdf)

Related Articles

Amen. Thank you!